New Boston Historical Society

New Boston, New Hampshire

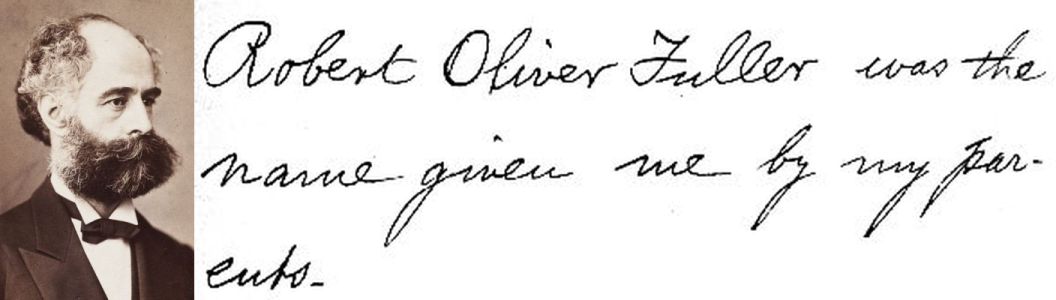

Robert Oliver Fuller in 1872

Robert O. Fuller and New Boston in the 1830s & 40s

Robert wrote, "How it came about that I went to N.B. I never knew." He suspected that it was the idea of one of his aunts, as his parents had difficulty providing for their children. Robert was put on a stagecoach in the company of Miss Cochran, a young woman from New Boston who worked in the Lowell mills.

Stephen Whipple had a store in New Boston village, but soon after Robert's arrival he "gave up keeping store and went into farming somewhat." Every morning Stephen woke Robert at 5 a.m. to drive the cow to her pasture a half mile away. Robert was barefoot all summer and remembers his feet were often cold. "After driving the cow, I had milk to carry morning and night, the pig to be fed, to bring in the wood, wash potatoes, wipe the dishes, sweep and dust," and so forth.

Robert cut cordwood and helped with haying. He'd be sent to unload the manure cart then to pick up a load of stones. (Again, Robert was only 7-14 years old when he lived in New Boston!) "In hoeing, I hoed two hills and skipped two, doing half a row to Mr. Whipple’s one row. That was half as much as a man. I was often told I did not earn my salt... I was a pretty tired boy at night. I was always hungry. I often had for my supper brown bread and milk. I disliked this very much. I think, however, it was the supper in many farmers' families. It was all the product of the farm and did not cost money." Robert also wrote of eating pork, baked beans, and hasty pudding, and said of the Whipples, "I think they lived better than the average of families." He wrote, "The fact was people had little money. The price paid for an able-bodied man to work in haying was $20 for a month rain or shine, or $1 per day for fair weather. Board included in both cases. Work was commenced at sun rise and did not always end at sun set."

New Boston's High Street today

Robert wrote, "I went to the village school about 10 or 12 weeks in the summer and the same in the winter. The most of what little education I have I received in the little red brick school house which still stands but, much to my regret, has been turned into a dwelling house." (We think this was on High Street.) "I think I learned easily and had no difficulty in keeping up with older boys." After dark the classroom "was lighted with tallow candles with turnips or potatoes for candlesticks."

"One night news was brought that a man had been murdered. There was great excitement. I knew the man that was killed. I can’t fix this date. I slept in a large unfinished attic. It was dark when I went up to bed, which was of straw on the floor. I well remember peering into the dark end of that big place wondering if the murderer who had escaped had concealed himself there. There was a roof of a building in the rear by which any one could easily reach a window that was without fastening in this attic. The terror of that night I shall never forget." (This may have been the murder of Charles Small by Elias Thomas in 1840 as Small was escorting Thomas home from a tavern. Small was due to be married three days later. "Intemperance caused the deed," wrote the Farmer's Cabinet.)

Fuller wrote, "The only newspaper was the Farmers' Cabinet, a weekly paper. It was rarely that I found anything in it that was of interest to me... What I longed for most after the first year or two was books. I was hungry for something to read. If I found there was a book I could borrow I would go miles to get it. If successful I felt that I had a prize and would go back light hearted hugging the treasure under my arms. I was not allowed to read novels. If the book was of that kind I kept it out of sight."

Stephen and Hannah Whipple had a baby boy when they were almost 40. "This arrival made quite an increase in my work." The Whipples had expected Robert to stay with them until he was 21, but their plans changed once they had children of their own. When Robert was allowed to return to Cambridge in 1843 at age 14, "it was a happy day."

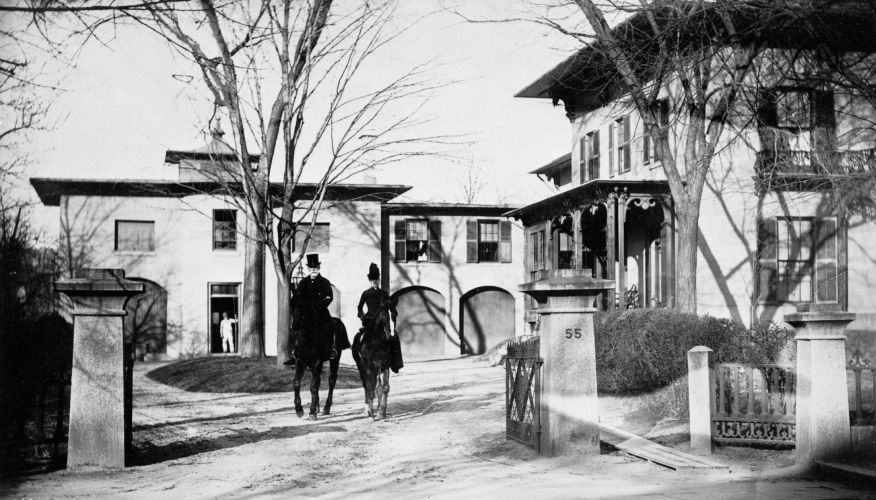

Mr. and Mrs. Robert O. Fuller at their Cambridge mansion — 1890

Robert returned to New Boston in 1897 and delivered an address at Old Folk's Day. He believed that his time in New Boston taught him the value of hard work and also contributed to his good health. (Robert Fuller died in 1903, aged 73.) He enjoyed reading books so much that he encouraged another Boston businessman to donate a library to the town of New Boston. That businessman was Joseph Reed Whipple, who supplied his Boston hotels from his Valley View Farm in New Boston. J.R. Whipple was the nephew of Stephen Whipple, and our town library is named after him.

The Historical Society is grateful to Bev Rodrigues, who transcribed the entirety of Robert's memoirs and gave us a copy.