New Boston Historical Society

New Boston, New Hampshire

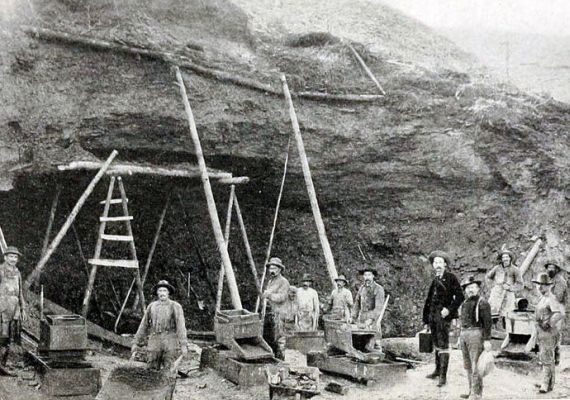

Six men from New Boston went to the California Gold Rush in 1850.

(This 1850 photo is of six other men.)

The Gold Rush: New Boston men go to California and the Klondike

Men left New Boston to join at least two of the major Gold Rushes of the 1800s: the California Gold Rush (1848-1855) and the Klondike or Yukon Gold Rush (1896-1899). This article was inspired and informed by Bob Todd's 2012 presentation "The Gold Rush: Great-grandfather James Todd's 1850s Adventures in the Gold Fields".What is a "gold rush"? A "gold rush" is what happens when gold is discovered in some faraway place and otherwise sensible men abandon their farms or their shops and their families to head for the gold fields in the hope that they might Get Rich Quick!

The prospect of wealth would be appealing to the young men of New Boston in the mid-1800s. The town's population had peaked in 1830 and the brief period of prosperity during the Great Sheep Boom had ended. The Erie Canal had just opened in New York State, and big Midwestern farms could now ship their produce to the east economically. Small towns like New Boston watched their young people move away to work in the new mills in Manchester and other big cities. For 28-year-old James Todd and his friends David Gregg and the Loring brothers, risking the money needed for a long journey to California must have seemed like a good investment. This is the story of how they came within 48 inches of a big gold strike.

James Todd and the California Gold Rush

In 1848 gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill, one hundred and twenty miles northeast of San Francisco. Over the next seven years, 300,000 people went to California in search of gold, or in search of the real fortunes that could be made providing for the needs of the gold-miners. To put that number in perspective, the total population of New Hampshire in 1848 was also around 300,000 people.

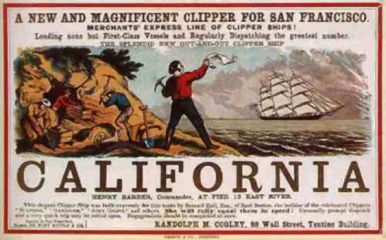

The easiest route from New Hampshire to the California gold fields was to take a ship 3,000 miles from New York to Panama, travel by canoe and mule through the jungle across the isthmus to the Pacific Ocean, and take another ship 4,500 miles to San Francisco, the port city nearest to the gold fields. (The Transcontinental Railroad wasn't built until the 1860s.)

The steamer Tennessee wrecked in fog near San Francisco a year after James Todd's voyage.

James Paige [Todd], son of Samuel and Betsey (Starrett) Todd, was born November 24, 1822, in New Boston, on the farm purchased and partly cleared by his ancestor, Samuel Todd. Here he grew up, attending the common school winters and working on the farm the remainder of the year.This article switched the names of the two steamships on which James traveled. The "Tennessee" was a famous Pacific Ocean steamer during the gold rush; the "Cherokee" sailed the Atlantic route from New York to what is now Panama.

[On] July 4, 1850, he sailed from New York for California in the steamer "Tennessee," in company with his brother-in-law, David Gregg, and John E. and Aaron F. Loring, whose sister he later married. In all there were about one hundred passengers bound for California. The passage of eight days to Chagres, Central America, was rough. From there to Cruces it was a trip of three days up the river in a "dugout" or log boat. Then a day and a half on foot brought them to Panama [City]. Here they took the steamer "Cherokee," and fifteen days later landed in San Francisco.

San Francisco grew from 1,000 to 25,000 people in three years. Its harbor filled up with abandoned ships as passengers and crew headed for the gold fields.

Thence they ascended the San Joaquin river to Stockton, and later to Jamestown in a sailing vessel. They took up a claim on Shaw's Flats and worked the placer diggings with pick and spade and a contrivance then well known to miners, and called a "long tom." [The "Long Tom" was a trough-shaped wooden box about 12 feet long with a screen used to separate flecks of gold from gravel that was shoveled into it. See a "Long Tom" in the photo at the top of this page.]

Here they wintered, and in the spring went to Sonora diggings and then to Columbia, California. In those days California was the newest country on earth, and many of its denizens were the roughest men in the world, gathered from the four quarters of the globe. Gambling and crime were rampant. Mr. Todd knew one gambler who remitted to his family each week $1,000 as the profits of the play for the week. He saw two Mexicans hanged for the murder of Captain Snow, of Maine. At another time the miners, angered by the daily thefts of the Digger Indians, attacked their village on Table Mountain and killed one hundred and fifty of them. Mr. Todd did not take part in this. [Thousands of Native Americans were killed during the Gold Rush or died after being displaced forcibly from their homes.]

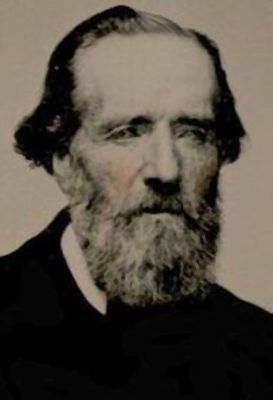

We don't know if James Todd, photographed after his return to New Boston, ever met the bandit Joaquin Murrieta in the California gold fields. However, the drawing Bob found of the Mountain Robber was too good not to use.

At Columbia he and his partners built two log cabins with cellars, which they afterward sold. Later the purchasers discovered very rich deposits of gold only four feet deeper than the cellars were dug.

Mr. Todd returned via Nicaragua in the spring of 1852, and arrived in New York on May 1. Returning to his home in New Hampshire he made the cultivation of the homestead farm his principal occupation, but was also engaged in cutting and sawing lumber, and also operated a cotton carding mill, which was burned. He has been selectman several terms, and deacon in the Presbyterian Church for thirty-five years.

Was the New Boston expedition to California a successful enterprise?

The biographical sketch of James P. Todd above describes how he just missed striking it rich when he sold his log cabins, unaware that there was gold beneath them. Overall, how profitable was the California expedition for the small company of New Boston men? Bob Todd said he has no records of profits or losses, but he described his great-grandfather as living the life of a gentleman farmer when he returned to New Boston. James paid for all eight of his children to attend high school at the Francestown Academy and sent six of them to college, which was unusual for that time.

Bob says that the New Boston men were lucky to discover a natural spring on the site of their claim, and thinks they made more from the sale of water than from the value of the gold they mined.

After James Todd returned to New Boston, the Loring brothers' luck ran out. John Loring died in 1852 on board the "Golden Gate" and was buried at sea. Aaron Loring died in Sonora, California in 1854. In her article "New Boston's Forty-Niners", Rena Davis wrote that the Lorings were two of the seven New Boston men who died in the gold fields or on their way to or from California. For example, the Dodge brothers James and Willard perished while crossing the isthmus of Panama; murder was suspected. Benjamin Russell drowned in San Francisco Bay in 1850. Rena wrote "There was no wharf at San Francisco to land passengers in those days and because of the excitement of reaching California, many people drowned in the bay before they ever reached shore."

On a more cheerful note, Bob told us that James Todd's partner David Gregg became the patriarch of another successful New Hampshire family. David's descendants include Governor Hugh Gregg and Hugh's son, Judd Gregg, who served New Hampshire as a Governor and a U.S. Senator .

A Letter from the California Gold Fields

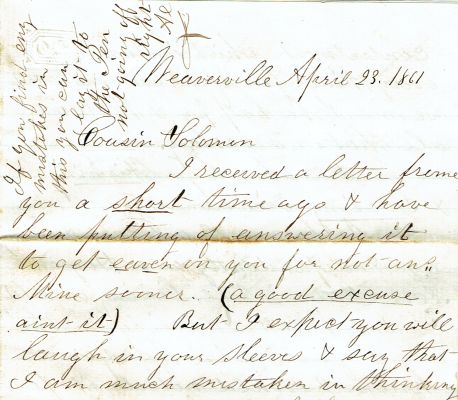

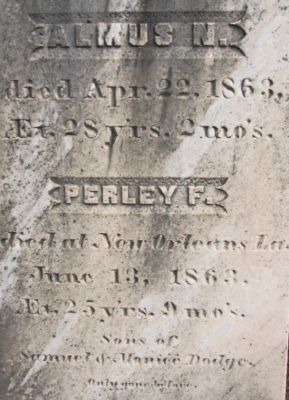

In 2014, Clem Lyon Jr. gave the Historical Society a box full of treasures including a letter from Almus N. Dodge, working in the California gold fields, to his cousin Solomon Dodge Atwood at home in New Boston. Excerpts from this 4-page letter suggest that Almus had quite a sense of humor. He was one of several brothers who were prolific letter writers. The notes which follow the letter explain what became of the Dodge brothers.

Weaverville April 23, 1861

Cousin Solomon

I received a letter from you a short time ago and have been putting off answering it to get eaven on you for not ans. mine sooner. (a good excuse aint it)...

So for me I am well & living as Independently as a Hog on Ice. I am still living on Old Sidney Hill & delvering in the Mud for Exercise, for you know I would not do it for anything else but still if I happen to notice a piece of Gold I just pick it up to see how many I can get & proberly you are awaire that it is rather necessary to have something of the kind in a fellows Pocket just for Ballast.

I have not washed up my Diggings yet & therefour cannot tell you whether I am dead Broke or not so I will post you on that some other time. I have been working five & six men for the past four months and shall keep on the same way until July or August then I entend to take out my years work all at once & it will take several loads of Pumpkins to pay any expenses & if the Pumpkins should not happen to be there I shall proberly join the Army & get revenge out of some of those Subjects of King Cotton which I think need a little bruising & will be pretty apt to get it unless they come to their sences pretty soon.

Levi arrived heare from the Sandwich Islands yesterday and he is pretty near as well as ever but a little stiff yet. According to his yarns the S. Islands are quite a romantic place & worth visiting. I would like to go there & if you will come & go with me we will start a Grocery Store...

My regards to Mr Whipple of the Firm of Atwood & Whipple. When you see Perley just tell him that Douglas has passed through California to Salt Lake...

I would write more but it is rather late & there is a School of Frogs just out of the door & they make such an awful nois that I must go & see if some of them don't need assistance.

Yours with Regards etc

Almus N. Dodge

Notes:

Notes:Almus Dodge was mining for gold, not growing squash. When he mentions pumpkins he means gold nuggets, recalling old Gold Rush rumors of legendary "nuggets as big as pumpkins".

When Almus writes of joining the Army to give a bruising to the "Subjects of King Cotton", he refers to the Civil War which began ten days earlier with the firing upon Fort Sumter.

Almus did not join the Army after sending this letter but he did have some success in the gold fields. While I was researching "Old Sidney Hill" I found a transcription of an August 1861 letter from a Maine gold miner named Emerson McCausland which mentions "The sidny hill boys is coming down monday A N Dodge has cleared between four and five thousand dollars this winter good for Al."

In 1862, Emerson wrote "Alvin(?) Dodge has been very sick in San Francisco all winter he has somewhat recovered and is on his way home." Almus died of consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis) in New Boston in April 1863, age 28.

In his letter Almus mentions his brother Perley. When President Lincoln called for volunteers, Perley F. Dodge was one of twenty-four New Boston men who enlisted in the 16th Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers. He died of fever in Lousiana, in June 1863. Many of Perley's letters from 1855-1863 are now in a Dartmouth College collection which "Contains correspondence home to family concerning his military service and personal issues."

Almus mentions another brother Levi, just returned from the Sandwich Islands (now called Hawaii). Almus's suggestion that he and Solomon should go there (Hawaii) to start a grocery store is one of his jokes: Solomon Dodge Atwood had opened his first New Boston general store the previous year at age 21, in partnership with J. K. Whipple.

Solomon's long career is documented on the General Store page.

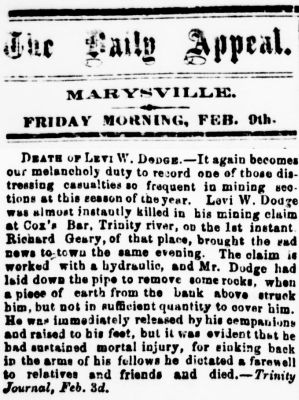

Levi Dodge died in a mining accident in 1866.

Almus mentions another brother Levi, just returned from the Sandwich Islands (now called Hawaii). Almus's suggestion that he and Solomon should go there (Hawaii) to start a grocery store is one of his jokes: Solomon Dodge Atwood had opened his first New Boston general store the previous year at age 21, in partnership with J. K. Whipple.

Solomon's long career is documented on the General Store page.

Levi Dodge died in a mining accident in 1866.

Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library has a collection of Dodge family letters with this description: "The collection contains autograph letters, signed from the Dodge brothers to family members. Letters from Almus N., John C., Levi W., and William W. Dodge to their sister Ellen, brother Samuel, and father, in New Boston, New Hampshire, document the brothers' life in California and their work in the gold mines, circa 1856-1866. The brothers write from Weaverville, California, Minersville, California, and Eureka, California, and topics include the California economy; local social life and schools; Levi's trip to Hawaii to treat his rheumatism; and Levi's and John's attempts to start an ice business. One autograph letter, signed, from A. J. Smith, discusses Levi's accidental death in the mines in 1866."

The Klondike Gold Rush 1896-1899

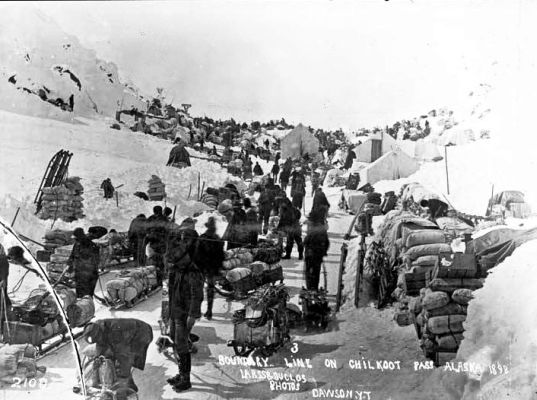

Conditions on the route to the Klondike gold fields were harsher than in California.

The California Gold Rush was just one of many 19th-century gold rushes in North America. There was an 1828 gold rush in the Georgia mountains ("Thar's gold in them thar hills!") and another in the Black Hills of South Dakota which led to Custer's Last Stand in 1876. The last discoveries of gold in the 1800s were in the Yukon Territory and Alaska.

If you drive to New Boston from Manchester along the Bedford Road, you know that a landmark is the hand-painted sign identifying Klondike Corner. Sandy Molloy wrote an article for the Historical Society explaining the history of this landmark:

Klondike Corner, at the intersection of Bedford and Chestnut Hill Roads, was named after the Alaskan Klondike during the Gold Rush years.

In 1896 gold was discovered in Alaska. In the two years following, people from all over the United States rushed to make their fortune and New Boston citizens were not exempt from this desire.

Clifford Dawson was one such citizen. It is not known whether Dawson struck it rich during his adventure, but I suspect not, as he later became a painter of bridges and trestles for the B & M Railroad. Nevertheless, when he returned to New Boston in the early 1900's he named the corner near his home "Klondike Corner", presumably in remembrance of his Alaskan adventures.

Dawson met his death on October 4, 1915, while performing his duties to the railroad. That day while he was painting a bridge, a train came along and he was either hit or jumped to his death to avoid it.

The Klondike Corner sign stands at the corner of Bedford and Chestnut Hill Roads. I use it as a landmark when giving directions to visitors from Massachusetts. I always advise them, "After you've missed the turn onto Bedford Road, turn around, come back, and take a left at the Klondike Corner sign." -S.M.

Klondike miners, c.1899. We have no photos of Clifford Dawson or his Klondike expedition.

The miner about to eat his shoe is Charlie Chaplin, who based his 1925 movie "The Gold Rush" on stories from the Klondike.

If any readers of this website have New Boston ancestors who went to a Gold Rush, we would like to hear their stories!