New Boston Historical Society

New Boston, New Hampshire

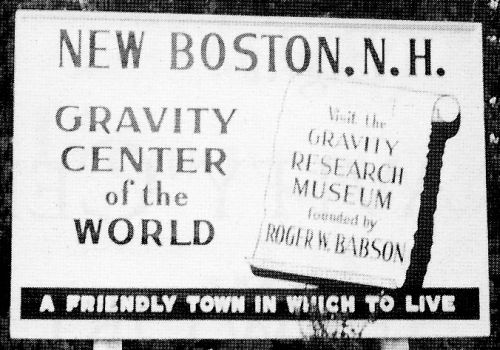

The Gravity Center of the World

Roger Babson and the Gravity Research Foundation

In 1948 Roger Babson established his Gravity Research Foundation "with the possible hope that some day the force of Gravity may be controlled." The Foundation was located in New Boston, because as its pamphlet explained: "Experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology advised a location which would be relatively free from damage should a bomb be dropped on Boston, Massachusetts, 65 miles away. A farm more than 100 years old was purchased and renovated, at New Boston, New Hampshire, for use as headquarters." Eventually Babson and his Foundation owned many properties including buildings on High Street, Mont Vernon Road and Hooper Hill Road.

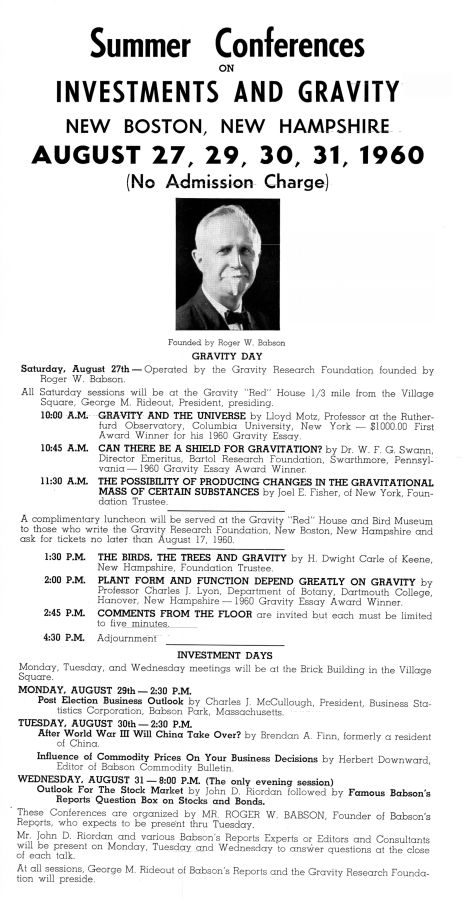

This 1960 flyer reflects Roger Babson's two interests: Investments and Gravity.

Babson's anti-gravity monument and the "Brick Building" mentioned in the flyer are across the street from the bank at the bottom of High Street.

The Brick Building was once a store and appears in our General Stores web page.

Monument honors quirky gravity researcher

Wealthy visionary bought large portion of New Boston in 1948 as safe haven from war

By DAVID BROOKS

Telegraph © 1998

NEW BOSTON - Of all the historical monuments that can be found in New Hampshire, honoring everything from Revolutionary War heroes to Robert Frost, perhaps the most surprising lies in New Boston.

On a flower-bedecked traffic island in the middle of Route 13, not far from the library and fire station, a handsome piece of granite draws attention not to the usual sort of historical event but to New Boston's role in "active research for anti-gravity and a partial gravity insulator."

It sounds like a joke, but it's really a monument to an unusual dream by an unusual man, Roger W. Babson, a famous financial analyst who came to this town 50 years ago this month [in 1948] because he thought it was remote enough to survive World War III, and who hoped to free humanity from the bondage of gravity.

Babson "was a genius," says Robert Bailey, 94, of Concord, a former principal of Goffstown High School.

In the summers of 1949 and 1950, Bailey was director of research for the Gravity Research Foundation, which Babson established in August 1948. It occupied what is now the Molly Stark Tavern, then a big farmhouse on Route 13 just south of the village center.

During its roughly 15 years in town, the foundation drew some big names and attention - much of it quizzical - but it never became the focus of research Babson had hoped. Nor did it become entwined in the community: Few people even realize that this month is the 50th anniversary of its founding.

During his time at the foundation, Bailey helped oversee an annual essay contest that rewarded innovative research into gravity - a contest so well-respected that famed English physicist Stephen Hawking submitted a number of papers, winning five times. Bailey also helped run the foundation's annual conferences, which drew upward of 75 people interested in gravity, affairs of the world and high finance. The main attraction of the foundation and the conferences was the nationally famous Babson, although this appeal did not always translate well in person.

Babson "was aloof," Bailey says. "He was very nice with me, very democratic ... but it was hard for him to connect sometimes."

"He was a kind man, very kind - a very positive person in opinions and actions," town resident Yvonne Gomes says. "But he was unusual."

Gomes worked for Babson for more than two years, running what he called his Information Center in a house just off the village center - one of a large number of buildings Babson bought when he came to New Boston in August 1948. Most of Gomes' work involved answering correspondence generated by Babson's syndicated newspaper column, which drew readers because of his fame as an economic forecaster. She eventually quit and went back to her job in a Manchester electronics factory because, she said, the work wasn't very interesting: It never developed beyond answering the mail. Like many of Babson's moves in New Boston, the Information Center sometimes had the feel of being a whim that never got finished, she said.

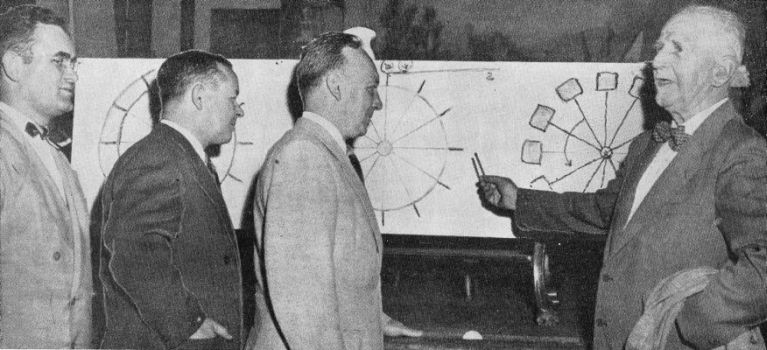

In 1949 Roger Babson shows how a gravity insulator might enable a Perpetual Motion machine to generate electricity.

(Photograph from "New Hampshire Profiles" magazine, June 1952.)

That memory is partly respectful, partly incredulous.

"It was a little far out," said Rhoda Clark, whose parents attended some of the foundation's summer meetings. "They had special chairs, like lounge chairs, and all during the meetings - my mother and father felt pretty silly - they'd sit with their feet higher than their heads because of gravity."

"I don't think the people in town took it seriously, to be honest," said Marion French, who worked at the foundation from its inception until she got married in 1954. "They took it as a side job for an eccentric.

"They liked (him) ... but, I mean, he was a far-reaching type, into the future. He was a visionary, and people have a hard time accepting that sometimes."

***

Babson was not the sort to be overly concerned about being accepted.He lived in Wellesley, Mass., and chose to come to New Boston in a typically unorthodox way:

After deciding nuclear war was all but inevitable and that everything near Boston was in danger, he took a map, drew a 60-mile circle around Boston and examined communities just outside the perimeter.

His choice was bucolic New Boston, partly because his mother had lived in Francestown. In 1948 he arrived in town, which had about 900 residents at the time, and purchased a lot of buildings.

"He bought half the town," Bailey said with a laugh. "That's where he got a not too favorable (reputation) with the townspeople."

"People were upset that he bought these old places and just let them stand vacant. Some of them actually fell down," longtime selectman Harold "Bo" Strong said. "That didn't make for good feelings."

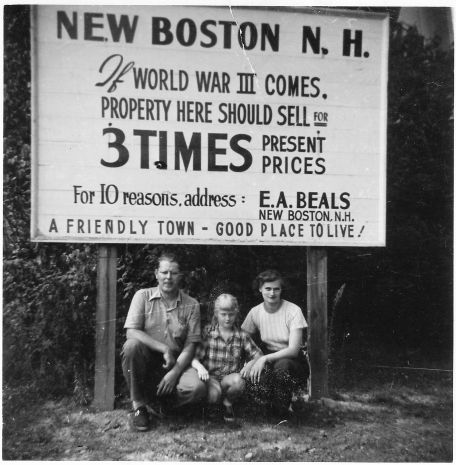

Babson also put up a sign declaring New Boston to be the safest town in North America if World War III came. Eventually it was toned down to read just that New Boston was a safe place to live.

New Boston was thought to be safe from a nuclear attack on Boston, MA, 60 miles away.

The Wilke family posed in front of this sign in 1950.

A Gravity Research Foundation pamphlet of uncertain date, copies of which are available at the New Boston Historical Society, says Babson and other foundations of the non-profit organization had considered opening a full-fledged laboratory in New Boston but eventually decided the foundation should "arouse interest and encourage others to carry on experiments in gravity research."

Such work could be on the fringes of science, especially when it sought to reduce or eliminate gravity. Einstein's theories of relativity had established that gravity is part of the basic structure of the universe, and most scientists believe trying to block it is like trying to block the passage of time - a topic for science fiction, not science.

An Aug. 10, 1948, clipping from a long-gone newspaper called The Union describes Babson's plans and demonstrates the unorthodox ideas that sometimes made Babson's quest the topic of derision: "Mr. Babson declared that this new 'insulation,' if discovered, could greatly reduce the weight of airplanes and increase their speed. He went on to say that even soles of shoes could be made with the 'insulation,' which would lighten weight in walking."

***

Babson's interest in gravity dates back many years and may have been partly triggered by the childhood drowning of his oldest sister in a river in Gloucester, Mass."They say she was drowned," he wrote in a book called "Gravity - Our Enemy Number One," "but the fact is that ... she was unable to fight gravity, which came up and seized her like a dragon and brought her to the bottom."

This interest overlapped another lifelong passion: Sir Isaac Newton, whose work on gravity is considered one of the greatest accomplishments of any scientist. Babson said he applied Newton's Third Law, commonly stated "for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction," to many areas of life, including his economic forecasts.

Babson became so enamored of Newton that he bought an entire room from Newton's last home in London and shipped it to the U.S., and also bought a bed from Warwick Castle in which Newton had slept. He also accumulated one of the world's best collections of Newton-related items, including Newton's death mask, which are now housed in the Burndy Library of the Dibner Institute of the History of Science and Technology on the MIT campus in Cambridge, Mass.

Babson became so enamored of Newton that he bought an entire room from Newton's last home in London and shipped it to the U.S., and also bought a bed from Warwick Castle in which Newton had slept. He also accumulated one of the world's best collections of Newton-related items, including Newton's death mask, which are now housed in the Burndy Library of the Dibner Institute of the History of Science and Technology on the MIT campus in Cambridge, Mass. In 1963, Newton's bed was placed in a Sir Isaac Newton Room museum in New Boston (it is now at Babson College). There it joined a collection of almost 5,000 birds that was inspired by interest in birds' voices by Thomas Edison, a Babson acquaintance.

Edison apparently never came to New Boston, but a number of other prominent men did, including Igor Sikorsky, who invented the helicopter and became a trustee of the Gravity Research Foundation, and Clarence Birdseye, who invented frozen food and founded the company that bears his name. (Photograph from "New Hampshire Profiles" magazine, June 1952.)

They attended some of the summer conferences at the foundation. A 1940s photograph of such a conference shows a line of big cars parked in front of what is now the Molly Stark Tavern, with large tents nearby to hold the crowd.

The Gravity Conference Hall seen in this 1959 photo is now (2012) Molly's Tavern.

***

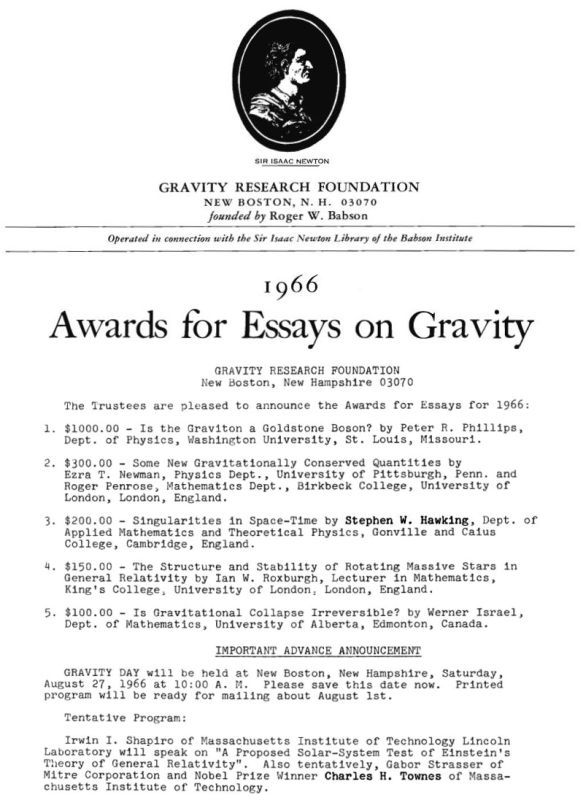

The annual conference was one of the foundation's three main purposes. The others were to establish a library of gravity-related papers and books, and to award annual prizes for essays pertaining to gravity.That contest attracted respected scientists who were investigating the nature of gravity. Few, if any, dealt with trying to block or eliminate gravity, which continues to be a fringe idea.

The most notable participant was Hawking, then in the process of developing the reputation that has made him one of the most respected physicists in the world. He won the prize five times from 1965 to 1971 for work on gravity and black holes. Hawking's graduate assistant at Cambridge University in England, Tom Auld, said recently that Hawking told him the prize "was regarded as a pretty prestigious competition."

The award was handed out as recently as 1996, when researchers at Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Institute for Experimental Physics in Hamburg, Germany, won $2,500 for a paper titled "Gravitationally Induced Neutrino-Oscillation Phases." Four other papers received monetary awards that year, as well.

By that time, the Gravity Research Foundation had moved to Wellesley Hills, Mass., where its longtime director, George M. Rideout, lived. Babson died in 1967 at the age of 88.

In 1996 the foundation possessed a post office box - but no telephone number - and an e-mail contact at the University of Cincinnati. Since then, however, it has disappeared from sight.

The post office box and e-mail address are no longer functional, and nobody could be found in New Boston, at Babson College or even at MIT, Babson's alma mater, who knows what has happened to it. [See the 2001 article below for an update.]

Many believe Rideout, who would be an elderly man by now, may have died, and the foundation passed on with him.

***

Such an end seems anticlimactic, but it echoes what happened in New Boston, where the Gravity Research Foundation, like an old soldier, just faded away."It didn't seem to have come to any conclusions," French said.

In fact, it's difficult to pin down exactly when the foundation did leave town. Apparently it closed around 1963, when New Boston was celebrating its bicentennial.

A June 1963 newspaper marking that bicentennial talks about the foundation as if it were a going concern, featuring an undated photo of Babson, Rideout and Sikorsky, but Clark, who moved to town in late 1963, says the foundation never held any conferences or appeared to be open while she was there.

By then, Clark said, the spread of hydrogen bombs apparently had made the New Boston location less important, since they meant World War III would destroy just about everything, no matter how remote. Babson also was well over 80 years old, perhaps less able to keep up with his varied interests, and decades of failed attempts to make headway against the burden of gravity may have lessened others' enthusiasm for the project.

The impact of the departure on New Boston wasn't as great as might be expected, say those around at the time, partly because the Air Force was installing a satellite tracking station in one corner of town that to an extent replaced Babson's group.

Further, the town's connection to the Gravity Research Foundation and other Babson projects had never been strong.

The foundation "was always a little separate," Gomes said.

Babson made sure his work wouldn't be forgotten here, though. He paid for the granite monument, which originally was on the Town Common but has been moved at least once in the decades since as part of redesigns of the village center.

Babson also left a trust fund to maintain the marker. As of the end of 1997, according to the town report, the Babson Trust had a balance of $2,692.

For many who were part of this unusual experiment, though, no monument is necessary. They still regard the Gravity Research Foundation and Roger Babson as a valuable part of New Boston's history.

"It didn't bring many taxes into town, or employment, but it gave New Boston a name on the map, brought people into town," French said. "It was interesting to be part of it."

Bailey, the former Goffstown principal, agreed.

"It was a very warm, pleasant experience," he said. "A very interesting operation. ... Am I glad I (worked for Babson)? Oh, my, yes. Absolutely."

Posted by permission of the editor of The Telegraph Copyright © 1997-98

In 2001, David Brooks updated his 1998 article to indicate that the Gravity Research Foundation was still in business -- only not in New Boston. Here is an excerpt:

Gravity exercise: What starts up in N.H. must go down to Mass.

By DAVID BROOKS, Telegraph Staff

Wednesday, June 20, 2001

The Gravity Research Foundation faded in New Boston after Babson died in 1967 and left a few years later. I couldn't find a new address despite some effort, so I concluded that it had passed away.

Then, last month, a graduate student in physics from Cornell University named Steve Drasco, who had found my old story on the Web, e-mailed me because he had seen references to the Gravity Research Foundation at the bottom of some current research papers and wanted to find out more.

Embarrassed, I hunted around and found that the foundation does, indeed, still operate. It is run in Wellesley, Mass., by George Rideout Jr., son of the foundation's original director.

Using money from what Rideout called a "modest trust fund" established by Babson, the foundation continues to hand out annual essay awards with a top prize of $3,500.

"The Gravity Research Foundation is neither 'anti-gravity' nor 'pro-gravity,' " Rideout wrote in an e-mail. "Our goal is learn as much as possible about gravity. Applications, if any, of the knowledge will emerge in due course."

Soliciting papers from within the physics community, it has had winners in recent years from Europe, the United States and Asia, including well-known names such as California astrophysicist George Smoot.

This year's winners were from Los Alamos Laboratory and the University of California-Berkeley for a paper called "The Cosmological Constant Problem in Brane-Worlds and Gravitational Lorentz Violations." That might sound crank-ish to the uninitiated, but it's deep in the heart of modern physics.

It's a shame, from this Granite Stater's point of view at least, that the foundation isn't still located in a small New Hampshire town. But it's nice to know, at least, that this child of curiosity is still around.

David Brooks' science column appears Wednesdays in The Telegraph.

Posted by permission of the editor of The Telegraph - Copyright © 2001

In 1966, the English physicist Stephen Hawking won third prize, $200, for his essay on "Singularities in Space Time".

The American physicist and Nobel Prize winner who was on the program for Gravity Day, Dr. Charles H. Townes,

and his wife Florence had a summer home on South Hill Road in New Boston for many years.