New Boston Historical Society

New Boston, New Hampshire

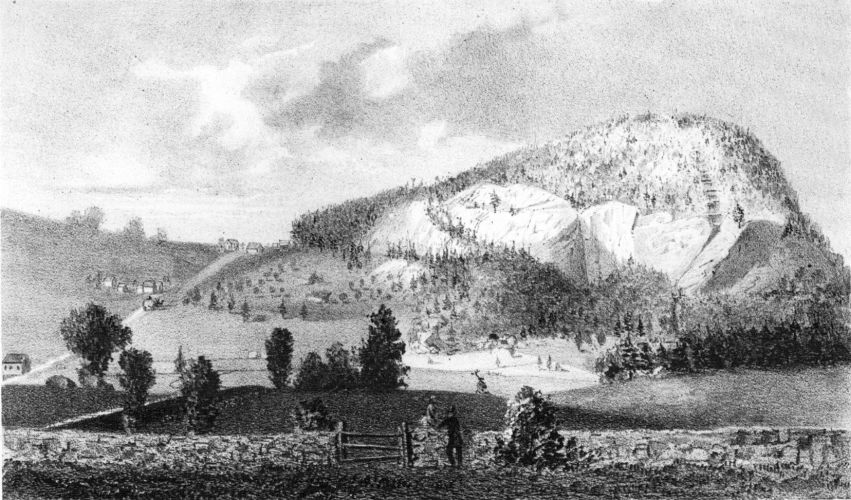

Joe English Hill

A brief discussion of a Native American, a big bomb, and an enormous antenna.

In "The History of Manchester" published in 1856, C.E. Potter tells how Joe English Hill got its name:

The hill terminates on the south in a rough precipice, presenting in the distance a height of some two or three hundred feet, and almost perpendicular. The hill took its name from an incident of olden time connected with this precipice.(The portrait of Joe from the "Joe English Echo", the 1927 yearbook of the New Boston High School, may or may not be historically accurate.)

In 1705 or 1706, there was an Indian living in these parts, noted for his friendship for the English settlers... He was an accomplished warrior and hunter [and] steadfast in his partiality for his white neighbors. From this fact the Indians, as was their wont, gave him the name, significant of this trait, of 'Joe English.'

In course of time the Indians, satisfied that Joe gave information of their hostile designs to the English, determined upon killing him upon the first fitting opportunity. Accordingly, just at twilight, they found Joe upon one of the branches of the 'Squog,' [i.e. the Piscataquog River] hunting, and commenced an attack upon him; but he escaped from them, two or three in number and made directly for this hill, in the southern part of New Boston.

With the quick thought of the Indian, he made up his mind that the chances were against him in a long race, and he must have recourse to stratagem. As he ran up the hill, he slackened his pace, until his pursuers were almost upon him that they might become more eager in the pursuit. Once near the top he started off with great rapidity, and the Indians after him, straining every nerve.

As Joe came upon the brink of the precipice before mentioned, he leaped behind a jutting rock, and waited in breathless anxiety. But a moment passed, and the hard breathing and measured but light footsteps of his pursuers were heard, and another moment, with a screech and yell, their dark forms were rolling down the rocky precipice, to be left at its base, food for hungry wolves!

Henceforth the hill was called Joe English, and well did his constant friendship deserve so enduring a monument.

Later in the 1700s and 1800s, many settlers of European descent arrived in New Boston. They cut down the forests, plowed fields and built houses and roads all over town, including on the slopes of Joe English Hill. In 1854, while on her way to Schoolhouse #3 which was built at the base of Joe English Hill, young Sevilla Jones was met by her rejected suitor Henry Sargent, who was armed with a revolver. But that is another story (see "Henry & Sevilla" on the Cemetery page).

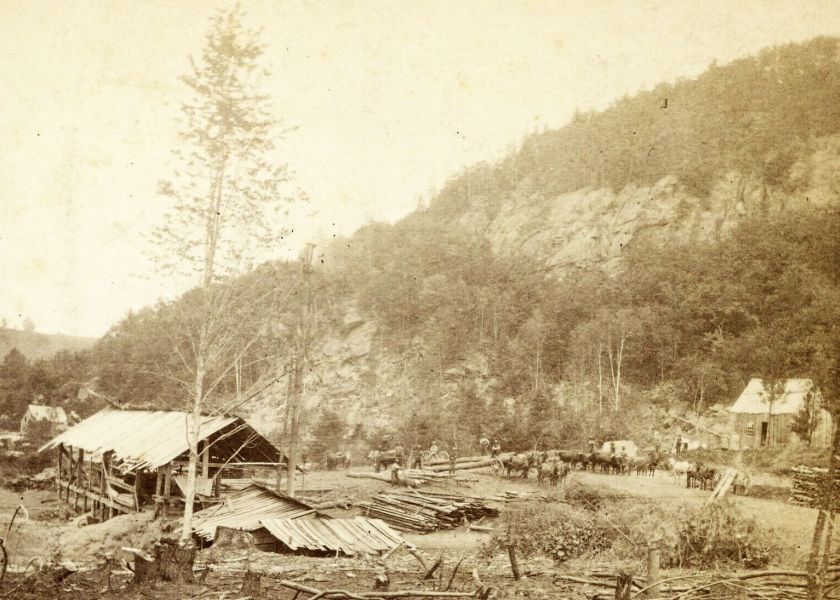

Saw mill at the base of Joe English Hill c.1880

Generally speaking, Joe English Hill and the nearby Joe English Pond were quiet New Boston landmarks until 1942, which is when the bombs began falling...

The Bombing of Joe English Pond

Update: In 2020, NBAFS was transfered to the United States Space Force and is now called "New Boston Space Force Station."

From an older version of the Wikipedia entry:

The New Boston Air Force Station dates back to 1942, when Grenier Field -- now Manchester-Boston Regional Airport -- was preparing to meet the demands of World War II.

On Sept. 5, 1941, Col. John Moore, commanding officer of the U.S. Army Air Corps at Grenier Field, wrote a letter proposing the government create a bombing range in New Boston near Joe English Pond. "The nature of the terrain around the pond is such that aerial bombing thereon would offer the elements of surprise, concealed approach and navigation to a point," Moore wrote. "It is believed that Joe English Hill (altitude 1,245 feet) would be a satisfactory stop for any ricochet bullets from ground machine gun targets."

Eventually, land belonging to 16 families, 12 of them in New Boston, was taken at a cost of $23,200.

There was no electricity on site, and water had to be brought from Dodge's store in the center of New Boston. Nail kegs were used as chairs. Locals felt so sorry for the soldiers that they donated used furniture.

During World War II, local residents remember watching fighters and bombers train at the Air Force station and learned to recognize the sounds of strafing and bombing as they went about their tasks.

"I'd watch from the kitchen window," 89-year-old Evelyn Barss told the Telegraph of Nashua newspaper in a 2005 story. "They would come in across the hill and drop their bombs and we would see them. These little black specks would go down, and you would hear a small discharge - they didn't use a lot of powder because it was scarce during the war."

In an article titled "The Bombing Range" written in 1963 for New Boston's bi-centennial, Oliver "Gus" Andrews wrote:

"The boys that were stationed at the range came from all over the United States, and many of them married New Boston girls."

He listed nine examples, including a young man from Maine named Oliver Andrews.

Gus married Lucille Kenney in 1943 and later became postmaster of New Boston for many years, and a Selectman too.

In an article titled "The Bombing Range" written in 1963 for New Boston's bi-centennial, Oliver "Gus" Andrews wrote:

"The boys that were stationed at the range came from all over the United States, and many of them married New Boston girls."

He listed nine examples, including a young man from Maine named Oliver Andrews.

Gus married Lucille Kenney in 1943 and later became postmaster of New Boston for many years, and a Selectman too.

Charles Peirce and his family called their house at the base of Joe English Hill "the Wigwam" for reasons unknown. The Peirce family home was taken by the Army Air Corps and used as lodging for the first soldiers to arrive at the new bombing range.

I read in multiple histories that water had to be brought to the Wigwam from Dodge's store until a well was drilled in 1942. I wondered how the Peirce family lived in the Wigwam for six years without any water. I asked Bea Peirce, whose husband George lived in the Wigwam as a boy, and she replied, "If they had five hundred chickens, they must have had water!"

Photo of "the Wigwam" under Joe English Hill c.1941 courtesy of Mrs. Bea Peirce. Is this the same house that's to the left of the saw mill in the 1880 photo above?

The U.S. Space Force installed a sign with the station's new name in 2021

A 2,000-pound general purpose bomb was found in Joe English Pond in 2010.

It was detonated safely by the Army Corps of Engineers.

"Unexploded ordnance technicians places explosives on a 100-pound bomb for detonation Aug. 21, 2013"

(US Air Force photos)

MEMORIES WANTED: If you lived in New Boston between 1942-1956 and have memories of the bombing range to share,

please e-mail the NBHS website editor, Dan Rothman:

townfarm@comcast.net

In November of 2013 I spoke with Vic, a veteran now living in Florida, who thought this web page should mention the Navy. Vic volunteered in 1951 during the Korean War and was based at Grenier Field which is now the Manchester Airport. During the Korean War, Navy air squadrons had to qualify at a bombing range before going overseas. Almost every morning Vic's team would go to the New Boston bombing range to maintain the targets. The targets were 55-gallon drums painted red, surrounded at 50 yard intervals by rings of trees that had been felled and whitewashed to make a prominent bull's-eye target. Vic's team would use a Caterpillar D4 bulldozer to skid the trees out.

The Navy used carrier-based planes (fighters and light bombers) which flew out of Quonset Point, RI. They would radio up to New Hampshire to warn that a flight was on its way. Vic and the other sailors would go to one of three steel huts to observe the target area through 6" x 18" slits cut in the 3/4" steel. They would report on the accuracy of the bomb drops to the fire tower, which would relay the results back to Quonset Point. Once someone forgot to notify the sailors in New Boston so they were surprised to see a plane diving at them while other planes were circling in the air. Some of the men dove under the bulldozer while the CPO shouted "get in the pick-up truck and get the hell out of here!" The pilots must have seen the men because no bombs were dropped. The 500-pound practice bombs did not have much powder in them.

Vic told me that there was also strafing practice at a field where some old tanks and trucks were parked. The fighter planes were not supposed to use tracer ammunition as the pyrotechnic charge might start a forest fire. When this instruction was ignored, Vic's team had to put the fires out using "Indian" fire pump extinguishers, shovels and brooms.

Vic and a 3rd-class Petty Officer enjoyed tapping maple trees at the bombing range. To boil off the sap they went to the mess hall and borrowed large coffee containers and built fires under them. They made gallons of sweet syrup.

Vic and the dozen other Navy men in his New Hampshire unit did not often see any officers visit from Quonset Point, except when they decided to "inspect the bombing range" which meant that they wanted to go deer hunting in New Boston.

2. A Bad Time to Go Fishing on Joe English Pond

In March of 2015 I received an e-mail from R. Wade Covill, MD of Columbia Falls, Montana.

Dr. Covill grew up in Weare, NH, and around 1947 his father was logging near the Bombing Range.

There were crews working in the range, so father and son believed there would be no bombing that day. Dr. Covill wrote:

In March of 2015 I received an e-mail from R. Wade Covill, MD of Columbia Falls, Montana.

Dr. Covill grew up in Weare, NH, and around 1947 his father was logging near the Bombing Range.

There were crews working in the range, so father and son believed there would be no bombing that day. Dr. Covill wrote:

Well, as a 12 year old with an obsession for fishing, I could not resist sneaking in to fish the pond! Rod in hand, I rode my bike into the range. Don't recall a gate, but if there was one, it was open (I think). Anyway, I got to the pond. Could hear heavy equipment working somewhere on the other side of the pond, but fortunately beyond my line of sight. I was on a shoreline devoid of vegetation, lots of junk littering the ground. Little canvas covered frames positioned about the area, looking much the worse for wear. The shoreline was easy to fish as it was pretty torn up. I caught a nice pickerel on my second cast, and thought I was going to have a great day, when I looked up at the hill between me and Manchester.

Diving straight toward me were three P47's in full attack mode. Thank God they didn't fire, with this dumb kid standing in the middle of the target area. Needless to say I didn't stick around to see what might happen next. In retrospect I doubt it was intended to be a live fire exercise, with work crews nearby. Little did I consider how much unexploded ordnance I must have tramped on. (Didn't our stuff always work?). Most of all, I still remember quite vividly what it feels like to be in the sights of three P47's on a strafing run!

P-47 photo from the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

3. Pheasants, Ducks, and Johnny Cash

In October of 2020 I received a phone call from Bill Harrell, a retired Master Sergeant from Las Cruces, NM. Bill served at the tracking station from 1967-1969, where he supervised the calibration laboratory. His duties included work on a wildlife commission; Bill's wife and daughter helped him raise pheasants from eggs in an enclosed area and ducks on Joe English Pond.

When I asked Bill where he served before coming to Grenier Field and New Boston, he told me that one of his first postings after he joined the Air Force in the 1950s was at the base in Landsberg, Germany, where his roommate was Johnny Cash, who like Bill was from northeastern Arkansas. The men were radio intercept operators who monitored Morse code transmissions. Bill said that John Cash couldn't sing very well or play the guitar at the time, but another roommate, Orville Rigdon, was an accomplished guitar player who tried to teach him the basics on a guitar Cash bought for twenty marks — about five dollars.

New Boston Space Force Station — Satellite Tracking

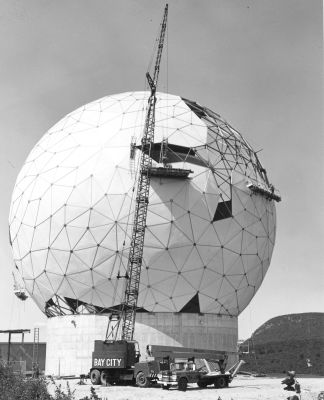

In 1959, the U.S Air Force began constructing on the former bombing range a "Satellite Control Network Remote Tracking Station whose mission is to provide tactical support to Joint Functional Component Command for Space by performing satellite operations 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. New Boston provides a real-time capability to users performing on-orbit tracking, telemetry, commanding and mission data retrieval services for more than 140 Department of Defense, national agency, National Aeronautics and Space Administration and allied satellites," according to the Air Force. It is not clear what the preceding sentences mean in English, but the mission is probably very important.

Photo of a "golf ball," designed to protect an Air Force Satellite Control Network antenna from the elements, under construction in 1960.

Joe English Hill can be seen in the background.

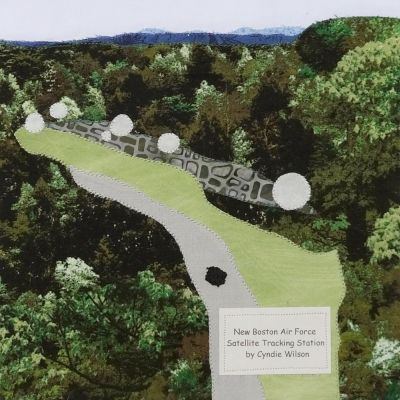

Today there are five golf balls, as depicted in Cyndie Wilson's quilt square for New Boston's 250th Anniversary quilt.

The newest golf balls are inflatable, not rigid.

The rock climber and extreme sportsman Dean Potter (1972-2015) learned to climb on the cliffs of Joe English Hill. A 2011 interview by Matt Samet published in Outside magazine included this story:

Potter began climbing in 1988, at 16, doing most of his apprenticeship near his home in New Boston, New Hampshire, on the granite cliffs of Joe English Hill, a 1,273-foot mountain that sits on federal land controlled by a local Air Force base.

DEAN POTTER: In the early days at Joe English, my friend John and I climbed a lot by pushing on each other's feet and pulling on each other's hands. Later, some older guys - the Adams brothers - ran into us and said, "Damn kids, you guys are going to die!" They told us to get a harness, and they said you can't use a laundry line for climbing. We were doing top ropes with stuff we got from John's father's garage.

PATRICIA DELLERT (Dean's mother): I wasn't aware of Dean's love of climbing until his high school years, when he was going over to Joe English Hill. I didn't know he was climbing on the cliff, because it's a military reserve, a satellite-tracking station. He was in there illegally. I thought he was just climbing the boulders below.

POTTER: My parents didn't want to believe their son was 200 feet up, free-soloing. They liked to go on long walks and runs, and they would go right by Joe English. Later they'd say, "Hey, we saw someone climbing up there." They would describe what they saw, and I'd be wearing the exact same outfit. And I'd say, "Oh... Nope, wasn't me!"