New Boston Historical Society

New Boston, New Hampshire

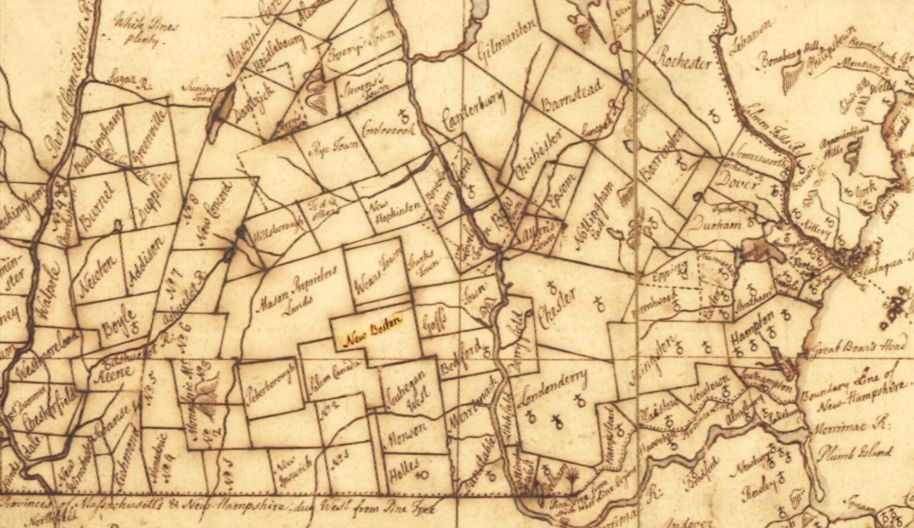

Excerpt from "An accurate Map of his Majesty's Province of New Hampshire" by Samuel Langdon 1756.

New Boston is just left of center in this map. Most of its settlers came from Londonderry, to the east.

Early Years: New Boston in the 1700s

Native Americans and the first European settler

Native Americans and the first European settler

The land which is now New Boston was inhabited by Native Americans for many centuries. Chester Price wrote in "Historic Indian Trails of New Hampshire" that the Pisga-tegu-ok Trail ran along the Piscataquog River from what is now Manchester through Goffstown, New Boston and Francestown. He translated Piscataquog as "to the place of the dark river" (pisga, it is dark; tegu, river; and ok, to the place). By the 1800s the three branches of this river would power up to 30 mills in New Boston.

We haven't much information specific to New Boston about the Namoskeag/Penacook and Abenaki tribes. We do know that when English settlers arrived in the 17th century, Passaconaway was chief of the Penacook whose lands included what is now New Boston. A drawing of Passaconaway appears to the left.

The New Boston story of "Joe English," a Native American who died in 1706, is told in the Joe English page. Also known as Merruwacomet, Joe may have been the grandson of Masconomet, a chief of the Agawam (Massachusetts) tribe who gave his children English names.

The first settler of European descent is believed to be Thomas Smith, who arrived in New Boston around 1735 from Ireland by way of Chester, NH. He built a log cabin on "The Plains" near what is now First Settlement Lane near the Gregg Mill Bridge. Smith had once escaped from capture by Indians, and when he saw signs of Indian activity near his New Boston homestead he returned to Chester.

The 1885 "History of Hillsborough County, New Hampshire" describes Smith's departure from New Boston:

One day, after planting, he discovered tracks, evidently made by a moccasined foot, and knowing Indians were still lurking in the vicinity, and were watching an opportunity to either take his scalp or carry him prisoner to Canada, he sauntered back to his cabin without manifesting any alarm, secured his gun and axe, and thinking Indians were in ambush in a direct route, he proceeded in a northerly direction to the north branch of the Piscataquog, thence up said river some distance before he ventured to take an easterly course, eventually reaching home [to Chester] in safety.

The First Grant

In 1736 the "Great and General Court of Assembly for His Majesty's Province of Massachusetts Bay" issued a grant to fifty-three men for a township of six miles square. The "History of Hillsborough County" states:

In looking over the records, we do not find any reasons why they should claim this grant; neither have we the petition, but we must go wholly upon supposition. The most probably and reasonable is, that on the coast of Massachusetts it was so thickly settled there must be some opening or avenue for the young men. These grantees were all Bostonians, and men of wealth and title; hence it would not seem that it was for themselves or descendants, but to improve the new lands and encourage settlement.

The first settlement was abandoned at some time between 1740 and 1747 due to the dangers of living in a New Hampshire frontier town during one of the French and Indian Wars. Nevertheless, the New Boston proprietors wished to continue their development of the township "notwithstanding ye many disappointments & losses we have sustained by reasons of warr in which most if nott all ye houses are burnt down." The first settler Thomas Smith was one of those who returned to New Boston.

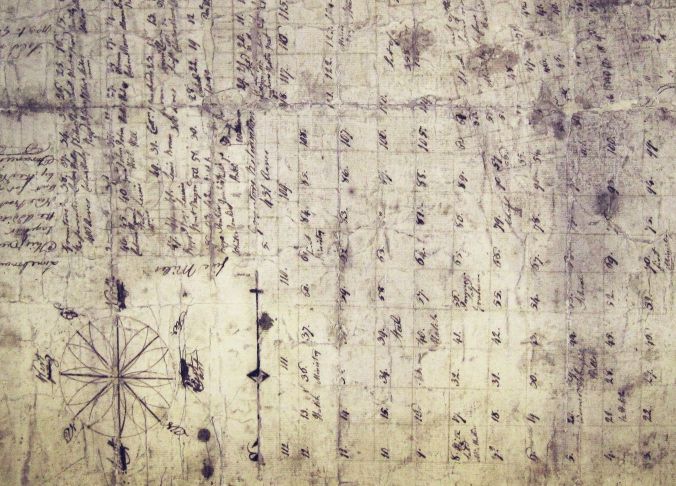

This fragment of a 1754 lot plan (rotated so that North is up) shows New Boston divided into many rectangular lots.

The most worn section in the upper right of this copy is where the first settlement and first mill had been built 18 years earlier.

The Second Grant

The early history of New Hampshire, which was separated from Massachusetts in 1741, is complicated by disputes over land grants. A second "Masonian" land grant was issued in 1751 which differed from the previous grant in that it included not only six miles square (36 square miles) but also a New Addition of 6 square miles that contained what is now Scoby Pond and some soapstone quarries. The New Addition was lost to New Boston when Francestown was incorporated in 1772. (The New Addition can be seen in the 1756 map of New Hampshire at the top of this page, protruding from the northwest corner of New Boston, and in the 1754 lot plan of New Boston just above.)

New Boston's First Settlement Today

In 2003 the Sargent Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology worked with the New Boston Historical Society to survey the area of the First Settlement.

Several cellar holes were identified which are consistent with houses and farm buildings of the 1730-1780 time period.

All that remains is stones and bricks.

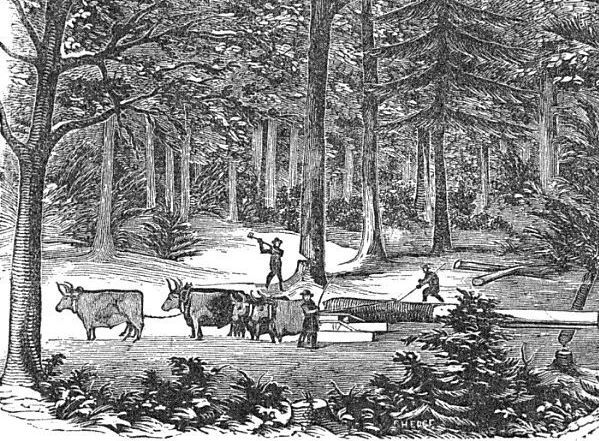

Illustration from "Forest Life and Forest Trees" by John S. Springer 1856

New Boston's early settlers made their living by logging trees, farming, or operating mills to serve the loggers and farmers.

The "History of Hillsborough County" explains that most of New Boston was forested except for the Great Meadow in the northwest part of town. The Great Meadow, still visible from Bunker Hill Road and Saunders Hill Road, was the only clear land in town:

It was of great value to the early settlers, having been flooded at some period by the beavers, which would destroy the timbers, and being abandoned by them, their dam went to decay, and after the water dried off, a kind of grass, known as the blue joint, sprang up and grew luxuriantly, affording a supply of hay to keep cattle before there was a sufficient amount of land cleared for that purpose.

Great Meadow Farm, established by Thomas Smith or his son Samuel, was farmed by Smith descendants for 200 years.

The enterprise was one of hardships and difficulty. The forest growths were dense and heavy, the surface broken and hilly, the soil rocky and stern.

Niel McLane provided these reminiscences about the early settlers in the 1897 "New Boston Old Folk's Day" report:

The first act after the purchase of a lot of land in the unbroken wilderness was the felling of the huge trees in the primeval forest and clearing them away by piling the logs and burning them and sowing the land with rye, or by planting corn between the fallen trees, where it grew luxuriantly.Many of the "huge trees of the primeval forest" had trunks of four to five feet in diameter!

The next move was to build a log house by cutting logs of equal lengths to form a square... placed on top of each other the height of six feet or more and then covered with pine splints. A stone chimney, an excavation for a cellar, and the ground floor constituted the dwelling of the early settler.

The first path from one house to another was marked by the seared trees. Afterward a tract of land was cleared to admit of travel with sleds, but not with wheeled vehicles. It required a great amount of labor to remove stumps and build a road in those days.

They were obliged to yard their sheep in a strong enclosure built of logs to preserve them from destruction by the wolves, who made night hideous by their howlings.

The first mills were built in 1736-1737 on the Piscataquog River near what later became Gregg Mill. A contract dictated the size of the dam to be built for a mill pond. There was to be a saw mill on the west side of the river and a grist mill on the east side. The saw mill was to carry a single saw suitable to saw lumber twenty feet in length. A lot of lumber was needed to build the 60 houses and a church required to fulfill the terms of the land grant.

Andrew Walker built a saw- and grist-mill in 1753. The custom of the time was that the miller would receive one-half of the boards for sawing or a sixteenth part of the grain for grinding. Walker's business practices were the subject of frequent complaints at town meetings. A later mill built on this site is now a private home at the intersection of Tucker Mill Road and Middle Branch Road.

Daily Life in the 1740s and 1750s

Within a few years after the First Settlement, it is believed that New Boston was abandoned by its early settlers, due to fire or Indian threat or both. But settlers returned in the 1750s, including Thomas Smith, whose descendents lived in New Boston into the 20th century. McLane wrote:

A census taken by the proprietors from September 20th to the 24th of the year 1756 reported "twenty-six men, eleven women, nine boys and thirteen girls," making a population of fifty-nine persons in all. The same committee reported "thirty houses, one dam and one saw and grist-mill, four frames and four camps, one house cut down, with one hundred and forty acres of improved land."

Previous to this date they suffered all the hardships and privations necessarily attendant upon a new settlement, living in log houses a long distance from neighbors, with no roads except a bridle-path through the forests, guided by marked or spotted trees, with the underbrush cut away, so that a horse might pass in summer, but in winter the usual mode of traveling was on snow-shoes. Tradition says that the snow fell to a greater depth in the dense forest than at the present time [1880s].

The house furnishings would not compare favorably with the drawing-room or parlor of the present day. They consisted principally of a very few cooking utensils, straw bed, etc. After the erection of saw mills they could procure boards to make tables and seats.

Their diet was of the plainest character, consisting mainly of soups, beans, or barley and rye, and Indian bannock [a flatbread fried in fat], and milk was added to this after sufficient land had been cleared so that they could keep cows. Meat was rather a luxury than an article of diet for every day consumption.

So far as animal food was concerned, it was procured from the forests. The deer remained in limited numbers, and bears were numerous, and as every man owned a gun, they could procure a supply of meat, particularly of the latter [i.e., bears], although not as palatable as the deer.

Another source from which to vary their diet was fish, with which the streams and ponds abounded to the degree that in the spring, when the suckers left the ponds for the brooks, in the spawning season, they could throw them out with shovels.

Their clothing was of home manufacture, spun and woven from the wool of the sheep or the flax raised on the farm. Manufactured articles and store goods had to be transferred on horseback or on a drag drawn by a horse. These goods came from the older towns on the coast.

We have no drawings of the "eleven women and thirteen girls" mentioned in the 1756 census of New Boston.

My photos of women in Colonial dress are from the Minute Man National Park.

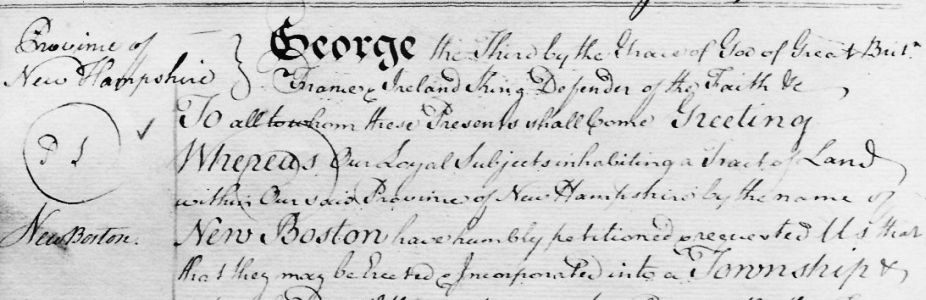

In 1763 the township of New Boston received its charter in the name of King George III.

New Boston pine trees provide ships' masts for the King's Navy

C.E. Potter wrote in the 1851 "The History of Manchester":

The valley of the Piscataquog has ever been noted for its excellent lumber, and in the time of the Royal Surveyors, a deputy surveyor and agents were always appointed in Goffstown and other adjacent towns, "to prevent waste in the King's woods." Masts of great size and of extra quality were cut on the "Squog" and its branches, for the King's navy... Some of the largest and most valuable masts ever cut in the Province, were cut in Goffstown and New Boston.

Elizabeth and Elting Morison wrote in "New Hampshire - A Bicentennial History" about mast pines that were 500 to 1,000 years old and which stood 150 to 200 feet tall. No trees of this size could be found in the British isles.

Sometimes ninety to a hundred oxen, hitched up in a double string, were needed to haul in a single mast sled, so heavy was the giant log. On long hauls, as many as six or eight oxen would die from exertion.

From the "History of Hillsborough County":

The banks of the Piscataquog, its entire length, a distance of ten miles or more, was lined with pines of a large size and good quantity.

Some fifteen or twenty years prior to the Revolution, the British government undertook to procure masts for the royal navy, from Concord and vicinity, by floating them down the Merrimack River to Newburyport; but in going over Amoskeag Falls most of them were broken. The project proved a failure, and was given up.

They next turned their attention to the Piscataquog and its branches as a better field of operation, and to give even better facilities for conveyance, built a road from Squog Village (what was then Bedford) to Oil-Mill village, in Weare. The road was known as King's Mast road, and the King's surveyor went through the woods and put the broad "R" on all pine-trees suitable for masts for the royal navy.

It was a capital crime for a man to cut on his own land any pine-tree twenty inches or more in diameter, and was punishable with a fine and confiscation of the lumber.

The export of mast logs from New Boston, Goffstown and Weare in the 1700s was a very serious business to the Royal Navy and the King's local agents. The Weare Historical Society has an excellent web page about The Pine Tree Riot of 1772 which preceded the Boston Tea Party as an act of rebellion against the King of England. The sheriff and his deputy attempted to collect fines from Weare log-cutters for illegally felling "mast-worthy logs" but the King's men were seized, beaten, then chased down Mast Road towards Goffstown! (The Weare historians indicate that men from other towns paid their fines meekly.)

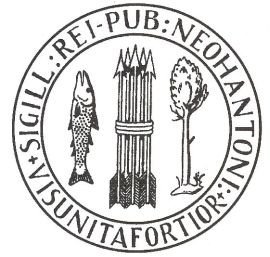

The first official seal of the new State of New Hampshire was designed in 1776 to show the state's two major economic resources, fish and pine trees, flanking five arrows which represented the state's five counties. The fish appears to be an Atlantic cod, not one of the trout which fly-fishermen now catch in New Boston's Piscataquog River. The motto "vis unita fortior" ("Strength United is Stronger") reflected the revolutionary spirit of the new United States.

In 1784 the New Hampshire state seal was revised to show the frigate "Raleigh" being built in Portsmouth NH in 1776 for the new American Navy. (The ship was powered by sails, of course. Those are not oars in the picture - they're planks supporting the hull while the ship is under construction.)

A State of New Hampshire web page summarizes the sad history of the frigate:

The Raleigh has a checkered career of adversities, while becoming the first to carry the American flag into sea battle. She was unable to go to sea for 15 months for lack of armament, and after her first voyage to France for munitions, her captain was dismissed for incompetency. Soon thereafter she was beached off Maine, captured by British warships, and used for the remainder of the Revolutionary War against her own country.

Think about this ill-fated ship the next time you see the New Hampshire flag!