New Boston Historical Society

New Boston, New Hampshire

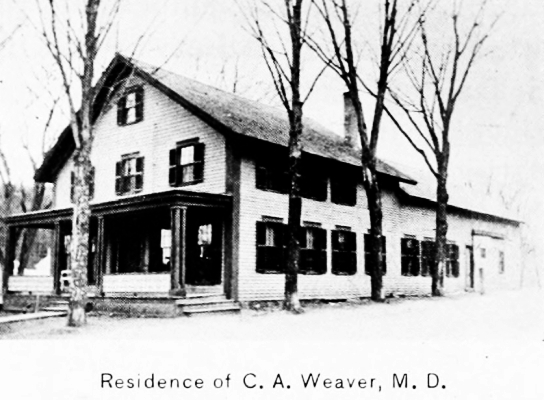

For sixty years this house on Route 13 at the bottom of Old Coach Road was the home and office for

two New Boston doctors: Dr. Charles Weaver from 1882-c.1912 and Dr. Sam Fraser from 1920-c.1948.

Chills & Pills - New Boston's Doctors

For over 250 years, New Boston has been served by a number of physicians and pill-dispensers. Today our town's medical professionals include some very talented women, but the early doctors described below - esteemed or otherwise - are all men. Dr. Thornton & the very young lady

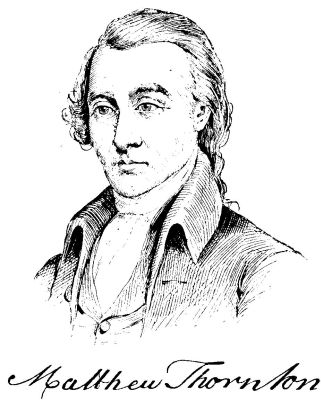

Dr. Thornton & the very young ladyNew Boston's first doctor was Matthew Thornton, who was a farmer and medical man here from about 1762-1770.

Cogswell's History of New Boston says that when he was 50 years old, "Thornton married Hannah Jackson, a beautiful young girl of eighteen years, whom he promised, when a child, to wait for and marry, as a reward for taking some disagreeable medicine."

The History is not completely accurate. Dr. Thornton was only 46 when he married the 18-year-old Hannah, and her family name was actually "Jack", not Jackson.

Perhaps you remember a popular Merrimack restaurant named "Hannah Jack's Tavern". Matthew Thornton moved from New Boston back to Merrimack in 1770, and later was one of three New Hampshire men who signed the Declaration of Independence. Too old to fight in the Revolutionary War, Dr. Thornton served in the first Continental Congress. After the war, he purchased a farm that had been seized from a British Loyalist, and it was this farmhouse that two centuries later became Hannah Jack's.

Note: Cogswell's 1864 History of New Boston and Cochrane's 1895 History of Francestown are the only sources that mention Thornton's residence in New Boston.

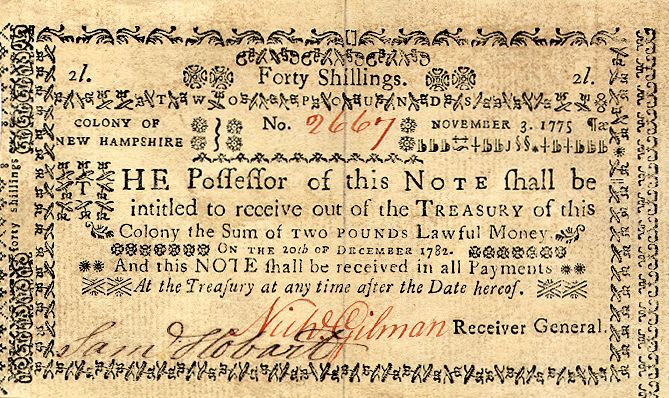

Dr. Gove & the counterfeit money

Dr. Gove & the counterfeit moneyDr. Jonathan Gove came to New Boston in 1770. During the early years of the Revolutionary War, Dr. Gove was a "Tory" or British sympathizer, and he was arrested for passing counterfeit money. At this time the new United States government was printing paper money to finance its war expenses. The British obtained a supply of the special paper used to print the American currency and began making counterfeit money to undermine people's confidence in the U.S. bills. A network of New Hampshire Tories, including Dr. Gove, helped circulate the fake currency.

As Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John, "A most Horrid plot has been discoverd of a Band of villans counterfeiting the Hampshire currency to a Great amount, no person scarcly but what has more or less of these Bills. I am unlucky enough to have about 5 pounds of it."

A boy looking for eggs in a Connecticut barn found some incriminating letters hidden in the hay, and the New Hampshire Tory gang was arrested. Dr. Gove went to prison for three months, but the people of New Boston petitioned the court to release him as he was the only doctor within 20 miles. "He was an excellent physician, and highly esteemed," according to Cogswell's History of New Boston. Dr. Gove was released, but he was arrested again the next year for passing counterfeit money and was imprisoned for a longer time. New Boston was a Tory town and Dr. Gove was readily forgiven and subsequently elected representative, town clerk and selectman.

Dr. McMillen - the carpenter who read medical books

A contemporary of Dr. Gove was Dr. Hugh McMillen, described in the History of Hillsborough County as a "self-educated physician and a good practical chemist" who did not bother to go to medical school or serve an apprenticeship under a trained physician, the usual paths to a career in medicine. Born in New Boston in 1763, McMillen was in fact "an excellent house carpenter; he was eccentric in character. He obtained access to some old medical books of Dr. Codman, at Amherst, and from them learned to compound certain medicines which effected some marked cures, gained for him some celebrity, and secured for him the popular title of doctor... It is said he discovered a cure for hydrophobia [rabies], if taken in season. The secret he left to his son, Dr. Abraham McMillen, and it died with him."

There is a letter in the National Archives written by Hugh McMillen in New Boston to President James Madison on the very day Madison was inaugurated in 1809. The Archive entry reads: "Has invented a system of medicine that will cure soldiers and sailors 'of all camp sicknesses' and seeks a government subsidy to manufacture and bottle his medicines." The Archive does not mention a reply.

Smallpox in 1792 - in which murder is narrowly avoided

From "The history of the town of Lyndeborough, New Hampshire" (1906) comes this tale of excitable New Boston neighbors:

At the present time one can have little idea of the horror and dread which the people had of the small pox in the early days of the settlement of the town. Vaccination was then unknown, and the physicians had not then learned to treat this disease. In some communities thirty per cent, of those attacked died, and sometimes the percentage was greater...

In 1792 a man whose first name was Joe, but whose surname is not recorded, was taken sick with the dread disease. He lived in a house in Lyndeborough near the New Boston line, in the northeast part of the town. This Joe's neighbors, nearly all of whom lived on the New Boston side of the line, were frenzied with fear and excitement, and a meeting was held forthwith to determine what should be done in the matter. It was advocated by the majority that, as the doctor had said that the man could not live two days, it would be the best thing for all concerned to burn patient and building, and thus avoid the danger of the spread of the contagion in burying him, and also the danger of the disease being carried by the wind; that the man was unconscious and a few hours would make no difference.

In excuse it may be said again that they were beside themselves with horror and fear. While they were planning to put the scheme into execution one or two cooler men mounted swift horses and started hot foot for the selectmen of Lyndeborough to see if something could not be done to prevent such a blot on the fair fame of the town. These selectmen... lost no time in getting to the scene of trouble, and by threats and pleadings soon succeeded in calming the excitement and preventing the threatened outrage.

Dr. Sam Fraser - a 20th century Country Doctor

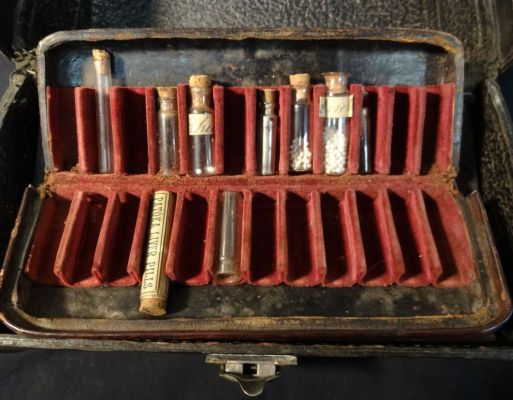

Dr. Sam Fraser - a 20th century Country DoctorDr. Samuel Fraser arrived in New Boston in 1920 and worked here for about 30 years. He claimed to have delivered 2,500 babies! Dr. Sam and his wife Mabel had four children of their own.

Dr. Albert Snay of Goffstown gave to the New Boston Historical Society a black leather case which is believed to have belonged to Dr. Fraser. In this case are vials of medicines which might have been used by country doctors like Dr. Fraser and Dr. Snay.

Arsenic may have been used to treat rheumatism, arthritis, malaria, syphilis, tuberculosis, and diabetes. Castor oil is a laxative. Tincture of Benzoin was used to treat sores and blisters or inhaled in steam to treat bronchitis and colds.

Some of the medicines below were prepared by New Boston druggists Frank Greer and his successor Ernest Hagland. "Pop" Hagland and his drugstore are featured in the Made in New Boston page.

Prohibition-era "Medicinal Alcohol"

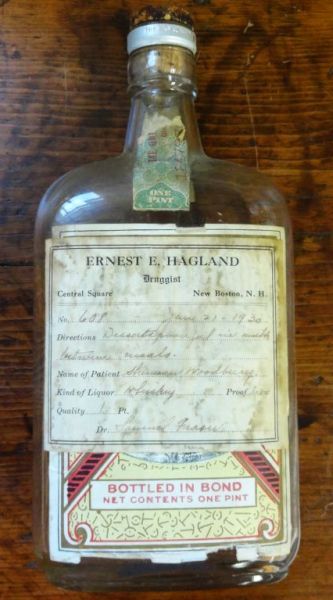

Prohibition-era "Medicinal Alcohol"While I was photographing medicine bottles from the Historical Society's collection, I was puzzled by this bottle (to the right). It looks like an ordinary whiskey bottle with a prescription pasted over its label. The prescription was written by Dr. Samuel Fraser in 1930, and this date gives us a clue about the bottle's historical significance.

"Prohibition", mandated by the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, forbade the manufacture or sale of alcoholic beverages in the U.S. from 1920 until the amendment was repealed in 1933. If a New Boston citizen wanted to acquire a nip of whiskey legally during Prohibition, "Medicinal Alcohol" was the solution. Dr. Fraser wrote this prescription for a pint of whiskey with the directions "Dessertspoonful in milk between meals". The patient, a Mr. Woodbury, was able to fill this prescription at Hagland's Drugstore a few steps away from the doctor's office, and whether or not he limited himself to a dessertspoonful is not known.

Daniel Okrent, the author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition has written about medicinal alcohol. He points out that the title character in F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby made his fortune by owning a lot of drugstores, from which he sold bootleg liquor during Prohibition. And in the real world, the founders of the Walgreen's drugstore chain worried about fire in their stores, because anytime the firemen were called "we'd always lose a case of liquor from the back."

Bootleggers and speakeasies in the big cities were associated with the criminal element. However, here in New Boston we can assume that the well-regarded doctor and druggist were simply demonstrating the independence that is traditional in the "Live Free or Die" state.